Science 101

How do we explore the world around us?

“Science”

“…[S]cience if often used to mean ordered knowledge concerning the things which occur in nature.” – The Lincoln Library of Essential Information, (c)1961

Science involves observing: watching, listening, feeling, sometimes even tasting and smelling. The scientist documents these observations, as they seek to both ask questions and find answers to these questions.

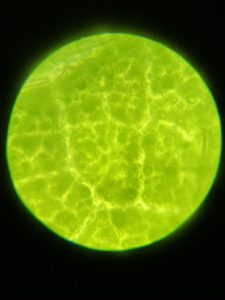

- Microbiology, the study of small, microscopic things, like bacteria

- Botany, the study of plants

- Zoology, the study of animals

- Meteorology, the study of weather

- Biochemistry, the study of how chemical reactions are involved in living systems

Much of what we know about how to raise plants starts with knowledge and understanding that was developed through science. Farmers, horticulturists and gardeners have experimented with different soil types, different lighting, different levels of moisture. They’ve observed where plants thrive in their native habitats. They’ve collected this information and passed it on, so that we, too, can begin to understand how to grow healthy gardens.

Biology

Biology studies the life around us, whether it is microbes, plants or animals. It helps to answer questions like “What is life?” or “What are plants made out of?”

Chemistry

Chemistry studies the tiny building blocks of matter around us – atoms, compounds and chemicals. Chemistry helps answer “What is stuff made out of?”, and “What happens if I mix these chemicals together?”. Chemistry looks at how matter can change into other kinds of matter, like hydrogen and oxygen becoming water.

Physics

Physics helps us describe and understand the physical forces and changes of matter. We can ask, “What happens if I warm this up more?” and “What happens when I drop this?”

Exploration of Creation

I have always loved science because it involves the direct observation of God’s Creation, instead of the creations of man. Science reveals order, intricate design, incredible complexity and stunning beauty. Each of these created by our infinite, powerful, and loving God.

When is the last time you paused to delight in God’s creation? When did you last feel that sense of wonder, as you observe something beautiful or intriguing in nature?

Romans 1:20

“

The Scientific Method

Nature is amazing to observe. Sometimes, though, we see something that makes us even more curious. It may be something we have not seen before, or a question of how something actually works. When it comes to using science to help answer some of our questions, we need a method to help us work through our questions, carefully and consistently.

When scientists come to a new question, they use the “scientific method” to help look for answers. Let’s look at how this works.

There are five essential steps to the scientific method:

01

Ask a Question

What are you trying to figure out? First you need to have a question in mind. Then you can figure out how to explore your question and find an answer

02

Develop a Hypothesis

A “hypothesis” is an “educated guess”. Based on what you know about your topic, can you guess what the answer to your question will be?

03

Design an Experiment

Now that you know what you’re trying to figure out, how can you best answer this question? To design an experiment, you will figure out the steps in the process to test your hypothesis and determine if you were right or not.

04

Collect Data

As you carry out your experiment, you will record the results of what happens.

05

Come to a Conclusion

Once your experiment is finished, review the data. Does it support your hypothesis? Or does it show that your hypothesis was wrong? Either way, you’ve successfully completed the “scientific method”, and you have new information that you can learn about and share!

Scientific Method in Action

Now, let’s try this out!

Now, let’s try this out!

Think about a plant that you could grow inside. A good example would be beans– they’re easy to find, sprout quickly, and grow large enough to be able to observe them easily.

You have observed that beans grow in places where they receive the following:

- Dirt, or some kind of “growing medium”

- Water

- Light

- Warmth (or at least to not be freezing)

Now that you have made some observations about bean plants, consider one of these growing needs, and ask a question:

“What is the best ____________ for growing my bean plants?”

The blank space could be “amount of water” or “amount of light” or “type of dirt”, or even “temperature”. When you decide which question to ask, you can then start to make a guess (your “hypothesis”) about the correct answer, and then design your experiment.

Here we go…

1. Ask a question:

“What is the best soil for growing my bean plants?”

2. Develop a hypothesis:

“If I grow bean plants in different types of soil, then they will grow best in potting soil.”

3. Design an experiment

Here’s an example of our experiment:

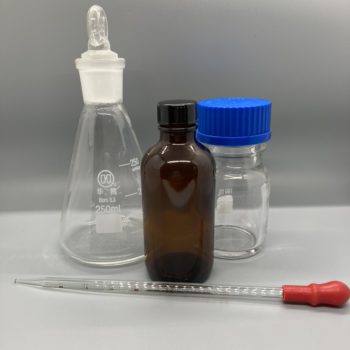

- Collect materials for the experiment: bean seeds, plant pots, labels, and paper for note keeping. Also collect different types of dirt: topsoil from the yard, sand, coconut coir, commercial potting soil, and gravel

- Fill each plant pot with 1/2 cup of the planting medium

- Plant two bean seeds 1/2-inch deep at the center of each pot

- Water each pot with 1/2 cup of water

- Place all the pots under a fluorescent light that turns on at 9am and off at 9pm.

- Water the plants each day with 1/2 cup of tap water.

- Observe the plant growth and write down what you observe every day for the next two weeks.

Hint for designing your experiment:

You want to keep all essential parts of your experiment the same for each plant, except for the one part that you are testing. This means that if I am concerned about soil type, then each plant will otherwise have the same container type, temperature, amount of light and amount of water provided. These common factors are “controlled” so that I know that differences in the plant growth and health are most likely related to the one thing that I am testing.

4. Collect Data

As you conduct your experiment, write down what you observe for each bean plant. Some of the information to note might include:

- How long does each take for the plant to sprout?

- How tall is each plant after two weeks?

- How many leaves does each plant have after two weeks?

- Did any of the plants die?

- Did any of the plants form flowers?

- Did any of the plants turn color, like yellow or brown?

- How much do the plants weigh at the end of the experiment (when removed from the soil and weighed on a kitchen scale)?

5. Come to a Conclusion:

After you run your experiment and record your observations, was your hypothesis correct? Did the plant in potting soil have more leaves, grow taller, or weigh more at the end of the experiment? Did it have better color or faster flowers?

If not, did one of the other plants seem to do better? Or were some or all of them similar in growth?

After your experiment:

Can you think of ways you could run the experiment differently?

Were there problems that you didn’t expect during the experiment?

Did you come across any other questions that could be answered with another experiment?